The Legend - Link Wray - Part 1

Here at Eastwood, we have always been big fans of the late Link Wray. Wray invented the power chord, the basis of most modern rock guitar playing, from rockabilly to punk to thrash and heavy metal. Most consider him to be missing link in the history of rock guitar and never really received the credit he was due.

We have some really exciting news coming between now and Christmas. Can't tell you much at the moment, but as we lead up to it, we are going to reprint (courtesy www.perfectsoundforever.com) this fabulous and detailed six parts series for your reading pleasure. Enjoy!

BE WILD, NOT EVIL:

THE LINK WRAY STORY

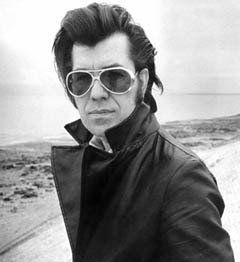

photo: Bruce Steinberg

A tribute by Jimmy McDonough © 2006

(part 1 of 6)

Link Wray seemed so strong, so invincible, like he'd be lurking around forever, just wailing away in some East Jesus shithole, terrorizing another doomed amp while he stuck the neck of Screamin' Red in the dazed faces of a new batch of converts. I guess I took him for granted. The music business sure did.

Link is the music for the midnight ride. No question about it, he sounds best when you have somewhere to go. Tearing down the highway in some shitbox of a car while blasting Link's guitar, some little chickadee flashing an inspirational bit of leg by your side--this is one of the great pleasures of still being ambulatory. That savage sound magnifies life's melodrama to a sublime degree. The night turns blacker, the moon more luminous, even her lipstick's a deeper shade of red. One could get all cutesy and call his music Ennio Morricone by way of a three-track-shack, but that would be dumb. You can't really compare Link to anything or anybody. He was an original to the death.

Crank up his version of "Hidden Charms" and it conjures visions of that dreamy bankteller you met just the other day, and how you'd like to waltz up to her window and present her with a gift-wrapped package of fishnet hose--cut low at the top, high at the bottom (in fact, I don't know see how we ever did without 'em). Or maybe it brings to mind a glorious dream of slamming your dusty cowboy boot in the fat face of that former boss over at the convenience store, the one who screwed you out of that vacation pay.

Who knows what evil lurks in the heart of men? Link Wray knew. Wray had been on both sides of the switchblade and knew neither end was very pretty. If you have any violence in you, any frustrated desires or uncontrollable urges, Link's your man. His instrumentals can unleash the bats in your belfry. Listen and you feel like you can hit the gas and outrun any cop, any creditor, any bad memory.

If you're bothering to read this, no doubt you read a postage stamp-sized obit or two that pointed out how Link's 1958 instrumental "Rumble" altered the sound of rock and roll. "It was such a definitive record, because it set the tone for so much guitar music that came after it," said producer and Strangeloves member Richard Gottehrer. "Except for rockabilly and country, at that time R & B, doo wop, city rock and roll was all saxophone solo driven. To hear a guitar played like that was outstanding, the power and the violence of it. Link came along and the guitar began to take over." Wray inspired Bob Dylan, Marc Bolan, Pete Townsend, Bruce Springsteen, countless others. Badass guitarslingers as disparate in style as Poison Ivy Rorschach and J. J. Cale namecheck him. It's hard to find a guitar player who hasn't been influenced by Link in some way.

Wray was the epitome of a certain sort of cool that continues to rev the engines of young upstarts the world over. "I just remember getting that Rockabilly Stars Volume 2 LP back in the early eighties when I was about thirteen years old," said guitar player Deke Dickerson. "There was a picture of Link, sneer on his face, big greasy pompadour, wearing a two-tone leather jacket playing a Danelectro Longhorn, with matching two-tone penny loafers. That picture changed my life. Link Wray, as far as I was concerned, was the coolest looking guy in the whole history of the world. And you know what I love about that picture? The two-tone leather jacket, the two-tone penny loafers, and the Danelectro Longhorn guitar--were all ordered out of the Sears & Roebuck catalogue!"

Of course, that's all real important stuff, but Wray deserves more. He was a hell of a lot more than some footnote in rock and roll history. Back in 1997, I interviewed Wray a bunch. After awhile, I got the feeling he felt he'd been too candid, and after a few more pickings of the brain, I never heard from him again. Not wanting to make Link's life any more complex than it already was, I vowed to sit on the interviews until he kicked the bucket. Now it's time to turn up the amp and let it rip.

MEE-MAW AND THE WRAY BOYS

The Link Wray story is really a tale of three brothers. Vernon Aubrey Wray (later known as Ray Vernon), the oldest, was a failed pop singer, an innovative producer/engineer and the shrewd businessman of the family. With his little cigar and omnipresent toupee, Ray had unlimited moxie. As Ray Men bassist Ed Cynar put it, Ray "could have sold new tires to someone without a car. He was always looking for a deal to make." Doug Wray, the youngest, was not only the prankster of the three, but a beast of a drummer who beat the skins until his hands bled. Bassist Ellwood Brown recalled playing a gig with Link at a used car lot and learning later "they could hear Doug's drums from three miles away. He was powerful beyond belief." Smack dab in the middle was Link, who unlike his fair-haired brothers, had inherited the dark dramatic visage of his Native American mother Lillian, known affectionately as Mee-Maw. "She always called me her little Shawnee baby," Link recalled. "Ray and Doug would complain, 'Well, momma never called us that.'"

Link Wray was a man who saw most everything as some form of God vs. the guy with the horns, and his birth on May 2nd, 1929, in Dunn, North Carolina was no exception. "I been in the grips of Satan ever since I been born. Because my mother was crippled, the midwife told my mother, 'Well, to save your life we gotta kill the baby.' And my momma said, 'Don't you kill my baby! I don't care if I die, you do not kill my baby!' So they took metal forceps to pull me out of her womb. I got scars on both sides of my head."

Just about everybody remembers the Wrays as a very unique, warm bunch--one "great big happy family," said Ruth Newton, who lived with them as an adolescent. "They were so close you could've woven a piece of string through them and made a broom, that's how tight they were." Fred Lincoln Wray Sr. was a pipefitter who received disability checks after a mustard gas encounter in World War I. "He was an abrupt old man," said granddaughter Rhonda Wray Sayen, chuckling. Wray Sr. loved his black eyed peas with bacon, and was only once served it minus the pig. "He took that plate, threw it across the room and said, 'There ain't no goddamn meat in it and I ain't eatin' it.'" According to Link, father and son weren't particularly close. "I loved my daddy. I guess me and him never got along. I was too close to my mom. He had a dumb ear to me. He was deaf tone [sic] to music. He couldn't sing, couldn't even whistle a tune, my dad."

Link's mother, Lillian 'Mee-Maw' Wray, was a handicapped Shawnee Indian beloved by all. Lillian "had a strong spirit but a weak body," said Link. "She got crippled when she was eleven years old--a white girl put her knee in her back, y'know, broke my mother's spine completely. I never heard her complain, not one time." When it came to Lillian and her children, the bond was ironclad. Link "got his fortitude, that never-die spirit from his mother," said Ellwood Brown. When speaking of Lillian, Link's voice "took on a different tone--it got real somber, almost like he was in church. Like you were talkin' about something holy."

After mother came God. While Link felt that organized religion was a racket populated with more shysters than the music business, the man upstairs was certainly not a force to be trivialized. Link had an elemental, no-frills, fire and brimstone relationship with Jesus. I once asked him if his was a vengeful God, and he quickly shot back, "Ya damn right. God can be anything he wants to be... and there's only one God--there's not two Gods, three Gods, that have these here four eyes and twelve arms and all that crap. There's just one power out there, y'know? God is the real big bang." Daughter Beth recalled her father coming in at bedtime with the big white family Bible, reading to her from wherever the book fell open.

Like so many other things in his life, Link's commitment to God came from his mother. "I wasn't a churchgoer. My mother never went to white church, never became a member of a church. She went to brush meetin's out in the fields. Me and Doug and Ray would play songs while she was preachin' while we were kids." Mee-Maw would preach and, according to Link, it was "frightening. Really frightening. Powerful. I knew my mother had somethin' special goin' for her. I saw a blue light around my mother, like an aura. It was her God, it was my God, our God."

Many saw otherwordly powers in Lillian. "I know my grandmother was a mystic," said her granddaughter Sherry Wray. " She'd tell me all kinds of things she'd see. She said if you saw visions, the Indians called it 'a treatment.'" For instance: one day Mee-Maw was walking with Link through a little path behind their home, and the two of them ran into a young black girl from the neighborhood. According to Link, Mee-Maw stopped in her tracks and, out of nowhere, said to the girl, ''You don't do it." Unnerved, the girl said, "Waddya talkin' 'bout, Mrs. Wray?" "You're gonna kill somebody," said Mee-Maw. "You don't do that." Link claimed the girl "was gonna kill her boyfriend. She said to my mother, 'I told no one I was gonna kill somebody--how did you know that?' My mom said, 'My God told me. It ain't worth it. You go on home, you pray and you forget about it.' That was my mother, man."

The Wrays lived hand-to-mouth in North Carolina, living in a side-of-the-highway shack Fred had built. "We were just born in a little hut--no floors in our house, just dirt, no electricity, just kerosene lamps and candles," said Link, who went to school barefoot, often without lunch. Lillian sold butter she churned, and Link recalled being sent to the store with chicken eggs to trade for other groceries. "You talk about pain? I'd go to bed cryin' cause I was hungry, y'know, and I'd hear my mother crying and praying. She'd say, 'Please, before you take me, let me live to see my kids grown.'

"I was from the poorest part of North Carolina--Dunn, where I was not white and it was not safe. Elvis was brought up poor in Tupelo, Mississippi, but he was still a poor white guy--and the whites ruled the world down south. My mother was a Shawnee down south, right? Ku Klux Klan country. Livin' amongst the black people, and they were livin' in misery, we were livin' in misery, and the poor whites was livin' in the same misery"--Link laughed--"but the only thing about it was the whites were hating us and the blacks.

"The Klan would come with their capes and burning crosses. I seen the sheets come, pull out the black people, tie 'em to a tree, and beat the shit out of 'em. We'd hide underneath the bed, hopin' they wouldn't come for us. It was just one big hell until my daddy got us outta there and to Portsmouth, Virginia, and that's where I saw a little better way of life."

Link was an odd little character. An early bout with the German measels left him with weak eyesight and hearing, not to mention, as he told Rob Finnis, "a wild stare." He lived in a dimension of his own and would pretty much remain there--decades later, musicians would tell tales of rehearsing with Link only to have it abruptly end, Wray's eyes glued to the TV, the guitarist lost in an episode of Batman. His school career ended in the eighth grade after an ex-sargeant assistant principal caught sixteen-year-old Link shooting spitballs in class, dragging him into the boiler room to exact punishment via horsewhip. "He started poppin' it beside my ear and I just saw red. There was a fire hatchet hangin' on the wall I pulled down. Ran him all over school with the fire hatchet, tryin' to kill him. Sorta like lost touch with my own brain, y'know what I mean? After I came to, I was out in the schoolyard with the fire hatchet in my hand. I just threw it down and ran home."

One thing entranced Link: music. Too poor to own a radio, Link would hear the sounds wafting out of a black family's house across the street and he soon fell under the spell. At age eight, Link encountered a black man named Hambone. "I was just out on the porch--my dad had bought my brother Ray a guitar, a Maybelle guitar with black diamond strings on it, great big old strings--and all Ray wanted to do was ride bicycles and go out, he didn't care about the guitar. So I picked it up. It wasn't even tuned, I didn't know what I was doin'. And this here guy comes walkin' across the street, 'Hey, boy, lemme tune your guitar.' So he tuned it up, started playin' bottleneck, man, and singin' this blues. I just fell in love with the music." Hambone was an orphan who'd been raised in a circus that set up tent in a vacant lot not far from the Wray home. "My mom and dad would take me to the circus to see the elephants and the tigers and then I'd say, 'I wanna see this black guy'--guitar, horns, drums, Hambone played everything. He was like a one-man show."

In 1943, the Wray family relocated to Virginia, living in government housing near the Portsmouth naval yards. "It was like moving from one world to a whole 'nother," said Link. "I couldn't believe it--all of the sudden I could turn on a stove and it was gas fire, I could turn on a switch and it was electricity." Work was plentiful, and a constant stream of sailors meant plenty of bars and nightclubs, which was a blessing for Link as he certainly wasn't day job material. "I got a job in the navy yard bein' a messenger for two months--enough to buy me some strings for my guitar and get started."

Link claims he was just fourteen years old when he joined a five piece jazz combo that included brother Ray on drums. "We were playin' like traditional jazz. Guy on piano, his name was Gene. He showed me all the minors, the augmented, all the right chords to play jazz." Then came a stint with a forty piece band "playin' Tommy Dorsey type of music for about four months. That got boring to me." Link paid to sit in with the Phelps Brothers, whose backing band included local whiz Chick Hall. "He was like a Chet Atkins. That guy was fantastic. I'd watch his fingers."

Link was obsessed. "I started listenin' to Chet Atkins, Grady Martin, all the Nashville people. I was tryin' to play country, play like Chet Atkins. I couldn't do it." Two big early musical influences on Link: Ray Charles and Hank Williams (Hank's mother was friendly with Link's parents; they attended brush meetings together)."He got the pain," said Link admiringly of Williams. "I loved his voice, the way he was in pain. I could tell through those moans, man, that he really meant it.He really meant what he was saying. And he was singin' out of pain, his old lady was fuckin' out on him, y'know, fuckin' everybody in sight--'Your Cheating Heart.' I really fell in love with Ray Charles more, even though he was jazzy. Just like Hank Williams, I could hear him moan. It just a struck a nerve in my heart."

The Palomino Ranch Gang: Shorty Horton, Link Wray, Vernon "Lucky" Wray, and Doug Wray circa the mid-fifties.

(photo courtesy Greg Laxton)

Wray's musical progress was interrupted by a 1951 stint in the Army that over the next two years take him to Germany and Korea. When he returned home, Link outfitted himself with a soon-to-be-very-significant combo made up of a 1953 Gibson Les Paul and a 30-watt Premiere amplifier. In 1954, the Wrays formed a country band that included two or more of the brothers, the Lazy Pine Wranglers, later to be Lucky Wray and the Palomino Ranch Gang. Along the way, they picked up Brantley 'Shorty' Horton, a standup bass player a few years older than the Wrays and a road dog who knew where all the good truckstops were. Doug Wray and Shorty had a rather special relationship. "Poor Shorty," said Ed Cynar. "Doug knew how he could get to Shorty every time. There were some magic words that, when uttered, Shorty would do exactly what they wanted him to do. Doug would say to Shorty, 'If you don't do whatever, you haven't got a hair on your ass!' That phrase resulted in a number of things happening, and one of them was Shorty showing up the next night with a mohawk haircut!" Ray was the very capable lead singer of the band and Link the sideman: "I was just a guitar player, Ray was the leader of the group, and I was happy with that."

The Wrays backed up such Western stars as Lash La Rue and Tex Ritter before relocating to Washington, DC in 1955. It was there they recorded their first handful of records at Ben Adelman's one-track Empire Studio, including Link's first vocal, a truly abysmal bit of rockabilly nothingness entitled "I Sez Baby," released to no acclaim on Adelman's sold-from-the-trunk-of-a-car Kay Records in January, 1956. Yet even in these first crude attempts one hears glimmers of the inimitable Link Wray style: the loping "Hillbilly Wolf" certainly has the spook. But Wray was destined for more than wearing a cowboy hat and playing 2/4 time. "I never did care for country stuff that much," admitted Link. "The drummer playing very light with brushes, the steel guitar waa waa waa behind it. It was too boring--like the jazz, I quit because it was so fucking boring."

As early as 1953, Link had noticed new sounds in the air. In the wake of Hank Williams death that year, his sister Irene invited the Wrays to Mobile to play a tribute show for her brother. While they were performing there Curtis Gordon, who'd been recording Western swing/hillbilly boogie numbers for RCA and was later to cut some rockabilly sides prized by fanatics, jumped onstage to join them. Something in his wild but pre-Elvis music and approach registered immediately with Link. "I saw the kids hollerin' and screamin' over this guy. He didn't have the rock and roll voice that Elvis had, but he had the energy--and the kids really hollerin'. I told Ray, 'That guy has somethin' these other country stars don't have, Ray, what is it?' Ray said, 'Well, the older people love the country stars--Ernest Tubb, Jimmy Dean. They attract the housewives, the workin' family. But the younger people love Curtis Gordon.' It made an impression, a long-lasting impression."

Back in Portsmouth, Link and his brothers had a daily gig at the Rathskellar. On Tuesdays, Ray's night off, Link began to experiment. "I just started makin' up my own little musical thing there--jazz up 'Tennessee Waltz,' have Doug play fast. Just play all the country songs with a beefed-up sound--I guess you could call it rock and roll, but we didn't know we were playin' it." The audience at the time, mostly drunken sailors, was less than enthusiastic. "We didn't get no tips! So Ray scolded me for that. But I was havin' a good time. I didn't give a shit."

So even before his 1955 arrival in Washington, DC, Link Wray was fumbling with some sort of rock and roll. But it would take a trip to the "death house" for Link to really cut loose. That, plus a visit from God and Elvis Presley.

(end of part 1)